Last week I covered a preseason game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the San Francisco 49ers. My first experience with NFL football came in the summer of 1980. I had just started working for a newspaper in Rochester, NY, and my boss asked if I wanted to cover the Buffalo Bills (note – if it’s a losing team, people are happy to let the new guy cover them). So this summer marks 34th year I’ve shot NFL football. A lot of things have changed in that time, but our job is still to make meaningful pictures. I thought you might enjoy reading about what goes into covering a pro football game.

With a game time of 7pm, I left home at 4. I’ve got to go early to make sure there aren’t traffic problems, to get set up in the photo room and make sure there’s an internet connection, and to shoot pre-game. There’s more to these games than just the action between the whistles. Pre-game warm-ups give you a chance to shoot isolated shots of players that can be used with stories about them in the future. It’s also one of the few times we get to shoot with “pretty” light here in Kansas City. Most games at Arrowhead start at noon, so an early-evening game like this means we get a short period of hard, angled light, which can be dramatic.

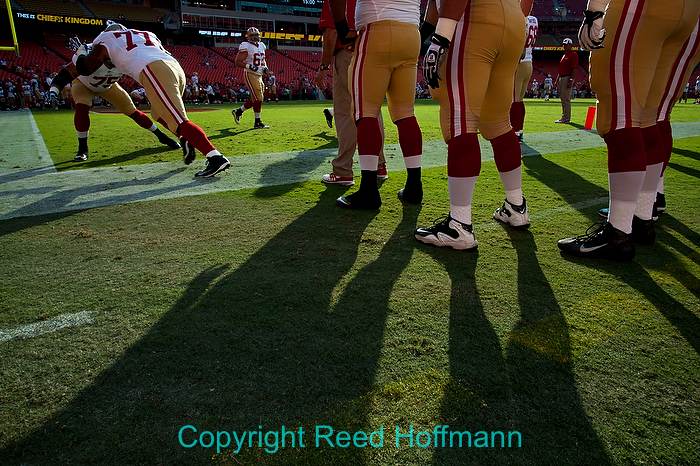

Pre-game warm-ups, a good time for feature photos, especially when you have nice light like this. Nikon D3, 24-120mm f/4 lens, ISO 400, f/10 at 1/500. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

The fans got warmed up too, and there were plenty of San Francisco fans, old and young, in the stands. Nikon D3, 24-120mm f/4 lens, ISO 3200, f/6.3 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Our access is fairly limited, and over the years has gotten worse and worse. By access I mean where we can shoot from, and when and where we can get on and off the field. Coming and going, we can only use the tunnel at one end of the field, at certain times. So you have to plan carefully to make sure you don’t get stuck inside or outside. On the sidelines, we’re allowed to shoot from the 30-yard line to the end zone on both sides, as long as we stay behind a yellow line about six feet back from the sideline. That wouldn’t be bad except for the fact that everyone else – literally anyone there – can stand in front of us. Officials, chain gang, ball boys, TV people (cameramen, sound people, assistants, friends of TV people), friends of players – you name them, they’re in front of us. The end zone can be a good place to shoot from, but not so much at Arrowhead. Here, the cheerleaders can line up in front of the photographers. Some people might enjoy that view, but not if you’re trying to make pictures of the game. So looking for a clean, un-blocked angle is what you spend a lot of your time doing.

With the 2X teleconverter, I can make tight action shots using an 800mm reach even though I’m not close to the action. Nikon D4, Nikon 400mm f/2.8 lens, TC-20EIII teleconverter, ISO 2000, f/5.6 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Important moments can happen far away, like this 105-yard kick-off return for a touchdown at the other end of the field, so you keep shooting and hope you can get a picture. Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens with TC-14EII converter (for 560mm), ISO 1400, f/4 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

For gear, you need top-of-the-line Nikon or Canon cameras and lenses. No other companies can compete with their autofocus, frame rate and lens choices for sports. Those lenses tend to be big and fast (wide aperture). The most popular lens is the 400mm f/2.8, and I use Nikon, of course. That might sound like a lot of lens (and it is, you need a monopod to use it), but when you think about how far we’re usually from the action, it’s about right. I often pair that lens with a TC-1.4 teleconverter, which gives me a 560mm f/4 lens. This time I also took along a TC-20, giving me an 800mm f/5.6 lens, and throughout the evening I shot with and without those converters. Even after dark, today’s top cameras can give great images at ridiculous ISOs (8000, anyone?). Those high ISO’s come in handy, as I’ve found that for high-action pro sports, 1/1600 is as slow a shutter speed as I like to use.

My main camera was the Nikon D4, which can shoot at 10 frames-per-second and has an amazingly quick and accurate autofocus system. The large battery easily powers the camera through an entire game, and the tough build will take a lot of punishment, including rain. Of course I also have a second camera, a Nikon D3, and I kept the Nikon 24-120mm f/4 on it. That’s in case action comes near me, or for other times I might need a wide-angle.

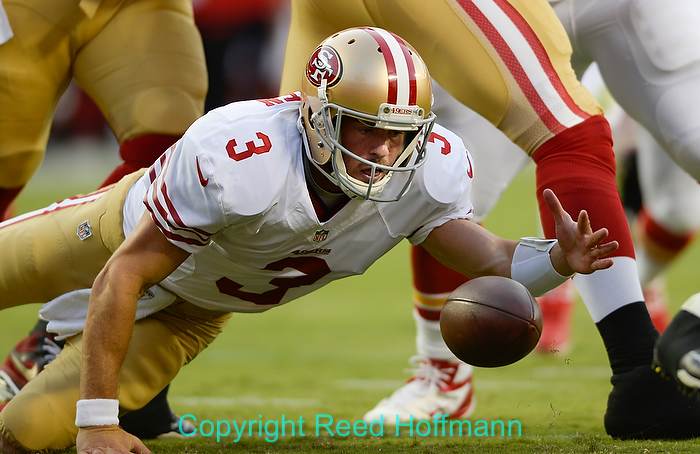

With San Francisco backed up near the goal line, I settled in behind the quarterback and hoped for something like this botched snap from center. Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 500, f/2.8 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

When possible, you want to be on the quarterback’s throwing side, so you can see the ball and his face, and any defender coming in. Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 1250, F/2.8 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Until the game starts I’m looking for feature pictures – fans, cheerleaders, stadium shots, players warming up or relaxing, etc. But after kick-off, the priority is action. Most people don’t realize you have to know the game pretty well to do a good job shooting it. Knowing the teams and players, what their strengths and weaknesses are, allows you to anticipate what might happen. You’ll see many photographers with earbuds in. That’s not music they’re listening to, but the play-by-play, which tells them about substitutions, injuries, and other details they might otherwise miss. It takes that kind of information to help you move to what will hopefully be the right spot to shoot from.

When possible, you want to be to the quarterback’s throwing side, so you can see the ball and his face. If it’s a running team, then being downfield a bit and shooting back gives you a chance to see the runner busting through, or around the line. If a score is imminent, you want to be near the corners of the end zone for the best view. Sports photography can often be thought of as a chess match – you need to be thinking ahead, and positioning yourself where you’ll have a clear view of the action.

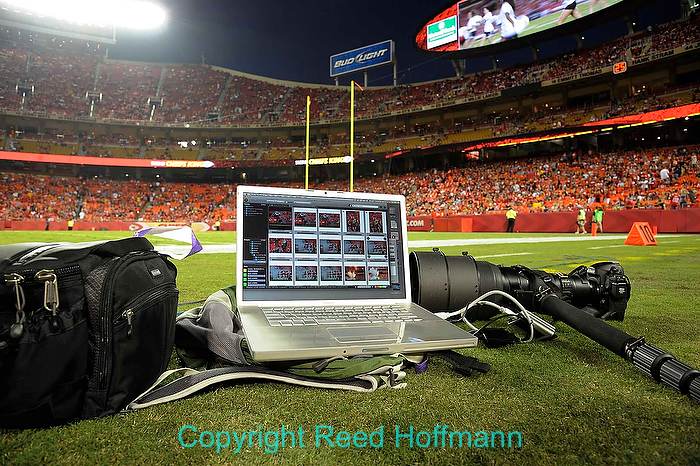

Downloading on the field during the halftime break means I don’t have to fight my way inside, and try to get out in time for the second-half kickoff. Nikon D3, 24-120mm f/4 lens, ISO 400, F/7.1 at 1/20 second. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

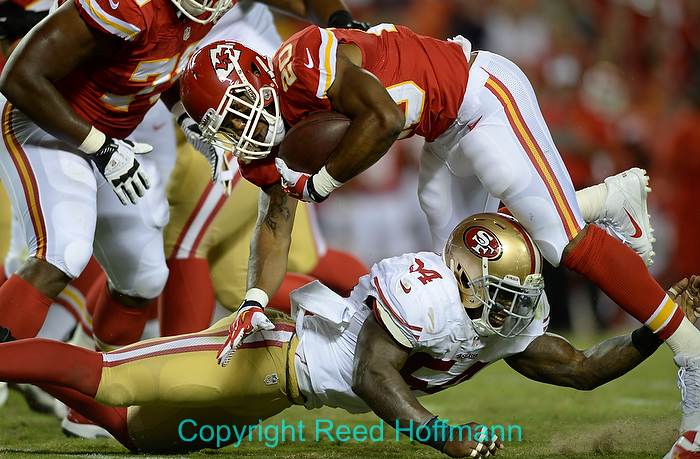

When a quarterback’s getting chased down, you’re hoping to see faces and reaction that will add emotion to the picture. Nikon D4, 400mm 2.8 lens with TC-14EII converter (560mm), ISO 2200, f/4 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

While most people think photographers just hold down on the shutter button and let the camera fire away, that’s rarely the case. Good photographers tend to try to shoot for the moment they want, and then perhaps hold down and run off a few frames of that sequence. If the mirror’s constantly flipping up and down, it can be tough to follow the play. And, despite having extremely fast frame rates, the best way to catch peak action is through anticipating and timing. In most sequences, my best picture is the first frame.

At halftime you have two choices – try to run in, download and transmit some photos before play starts again, or stay on the field. You only get about 15-minutes, so when possible, I prefer to stay on the field. I can carry a small laptop in a backpack with card readers (I usually use two to speed things up). I can unpack that and have it downloading before I would get to the photo room inside. And, more importantly, I’m already out there when play resumes. You’d be surprised how many photographers aren’t back on the field at the start of the second half. Most are still inside, praying nothing important happens until they there.

Every time a team punts, you want to be in a position where if it’s blocked, like this, you’ve got a picture. And then you thank God for being lucky! Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 1600, f/2.8 at 1/1600. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

You’re always looking for tight action, and then catching a peak moment. Collisions that send players flying through the air are always good. Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 1600, f/2.8 at 1/2000. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

While action is the priority, you also need to pay attention to the coaches and players on the sidelines, as well as looking to the fans occasionally. There are pictures to be made there too. When the game ends you’re looking for any final pictures, often of players meeting in the center of the field. In this case, Alex Smith played for San Francisco last season, so some of his former teammates found him to say hello.

When it’s all over your main concern is to get those photos out as quickly as possible. Most of us use Photo Mechanic (Camerabits.com) because it’s simply the fastest browser out there. We use it to batch caption during the download with the key information, then quickly go through finding the best photos. “Best” means photos that are key to the game – scores, turnovers, injuries, quarterbacks, coaches, etc. You don’t have time to spend much time fixing exposure or color, so shooting it right is very important. Probably the most difficult part of that process is caption writing. Everyone that’s clearly visible in the photo needs to be ID’d, and there’s a lot of other info that needs to go with the photos so they can be found easily in searches. It does you no good to make great pictures if no one can find them. There are always two edits going on – one for photos that are important to that game, and another for photos that might have a future life. More of my pictures get used in the weeks and months after the game than in the first twelve hours. And those captions and keywords make that possible.

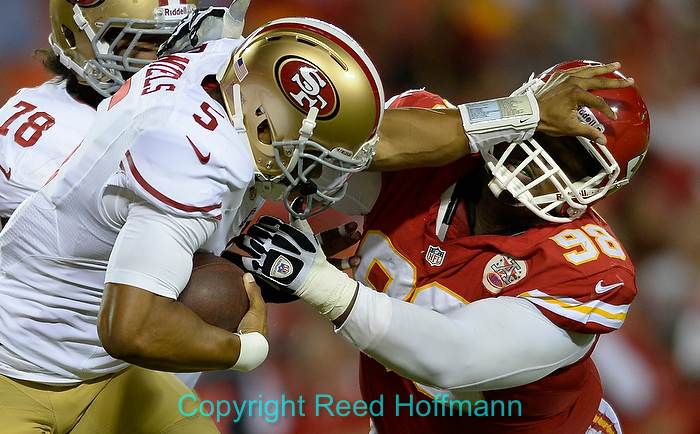

Tight action again, cropped tight too so you can really see the quarterback pushing the defender’s head back as he stiff-arms him. Nikon D4, 400mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 1600, f/2.8 at 1/2000. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

There’s almost always more to the story than just the game. In this case, Kansas City’s new quarterback, Alex Smith (11) was playing his first game against his former teammates. They visited after the game. Nikon D3, 24-120mm f/4 lens, ISO 1800, f/4 at 1/1250. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

At the end of the day – or night in this case – you’ve usually worked about nine hours, shot over 1000 pictures, and transmitted 50-100 of those. It’s a far cry from when I started in 1980. Back then I was shooting black and white film, perhaps as many as eight rolls in a game (under 300 photos), and printing 10 or 12 of my best. Captions were typed on paper and pasted onto the prints. If no one swiped them from the paper’s library, they might even be there five years later. Of course, few things are the same way they were thirty years ago. Not the game, not the way we cover it. Times change, we change and adapt. Despite the challenges, I still enjoy the work. And with luck, I’ll be doing this for at least another decade. Who knows, someday I might be writing about having shot NFL for fifty year. I sure hope so!