There’s nothing worse than not having faith that your gear is working properly. For photographers, the worst-case scenario is questioning the autofocus. A few years ago, one of the major manufacturers had a top-of-the-line body whose new focus system occasionally missed. That in itself isn’t unusual, since no AF system is perfect. In this case, though, there were certain situations that would always trip it up. The company responded with updates, and then a new system in the next generation, but the damage was done. Every photographer I knew who had that camera lost faith in it. And then worried that the next camera might have the same problem. That started a new trend in the industry, giving the user the ability to actually adjust the autofocus themselves. Nikon calls it “Autofocus Fine Tune,” Canon “Microadjustment,” Sony “Micro Adjustment,” and so on. The question is, do you need it?

In the last 18 years, I’ve had two times where I really, truly needed that feature. The first was in 2000, when one of my cameras had a sensor that was slightly out of alignment. At that time, though, there was nothing to be done other than send the camera in for repair. The second time was a few years ago when I was leading a workshop in Africa. Reviewing images after the first day, I could see that the focus with my long telephoto lens was off. In other words, on both cameras I could see that the focus was slightly behind the subject. As it turned out, that lens needed its optics adjusted. Since there was no repair service in the Serengeti, I was lucky that one of my cameras offered in-camera autofocus adjustment. Dialing it to the max, 20, I was able to pull the focus back in to the subject. Thankfully I realized that after the first day, and after that only used that lens on the camera that had the adjustment. After returning home, I sent the lens in and had it repaired.

If you were going to see a problem with autofocus, this would be the place – tight framing with an 85mm f/1.4 lens wide open. In this case, though, I can’t imagine the image being any sharper. In fact, I needed to soften the image in post-processing to avoid seeing every pore in the skin around her near eye, where I’m focused. Nikon D7500, ISO 200, 1/2500 at f/1.4 , 0.0 EV, Nikkor 85mm lens. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

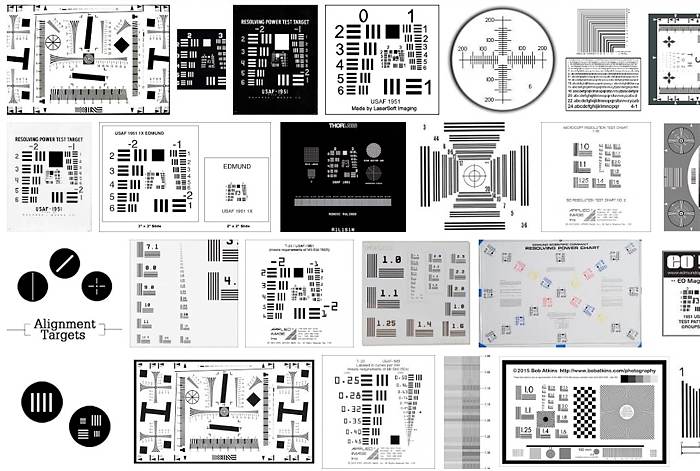

So in my experience, adjusting autofocus isn’t something I’ve found very necessary. However, I don’t have super-fast lenses (no f/1.4) and rarely shoot my lenses wide open (at maximum aperture), which is where people tend to see problems if they exist. That and when shooting tight, where depth if field is also limited. When someone asks me about this, my response is always the same: test to see if you really have a problem before doing anything else. To test properly, you need to remove as many variables as possible and strictly control your set-up. That means having the camera mounted solidly on a good tripod, using a relatively high shutter speed (I’d want a minimum of 1/500) and a subject that easily shows in or out of focus (there are plenty of test targets online that you can download and print).

If you want to give it a try, then here are links to a couple of in-depth stories by photographers that take this seriously. Both center on the Nikon system, but what they’re showing can be applied to any camera that offers adjustment. The first, a video by Steve Perry, shows a simpler, less expensive method. The second, a story by Nikon Ambassador Joe Terrill, is a bit more involved and shows how to use a system that costs about $200.

Personally, after reading both of these, I’ll go ahead and follow Steve’s method to adjust one my cameras with a few of my fast and long telephoto lenses. If I see a difference, then I’ll work through more of my cameras and lenses. After all, while I’m happy with the performance of my AF now, if it can be better, great, I’ll take it!

(If you like this, please share it with your friends, and let them know about the links about photography I post on my business Facebook page. I’m also on Instagram and Twitter, @reedhoffmann)