One challenge all photographers face is trying to find new ways to shoot the same thing. While covering basketball may sound fun (especially a pro or college team), that long season of many, many games can get repetitive and even boring. With limited places to shoot from at courtside, most photographers start looking up. One possibility is to shoot from the stands, if they have enough lens. Up higher, though, things get even more interesting. Let’s look at why a photographer might want to do that, and how.

Charlie Riedel is an Associated Press staffer here in Kansas City, and one of his regular assignments is covering University of Kansas basketball games. Courtside, his only choice is to shoot from one side of the basket at either end of the floor (all other space is taken by team, officials, other media and cheerleaders). Now that’s not a bad place to shoot from, as you can use one camera with a shorter lens (24-70mm f/2.8 or more commonly the 70-200mm f/2.8) for the near basket and a longer lens (usually a 300mm f/2.8) for the far bucket. There are some drawbacks, though.

From court level you have a good view into the players faces when they dive to the floor for a loose ball. And when they’re dribbling it’s a good angle too. When they’re shooting and rebounding, though, you’re shooting up at them. Which can create problems if there are bright lights from concessions or advertising, or even lighting in the stands, which can ruin your backgrounds. The biggest problem, though is something that moves – the refs.

Sure would have been nice to see the other players going after this loose ball. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

If you shoot sports much, you’ll develop a real dislike for the refs. Nothing personal, but they sure ruin a lot of good pictures. Yes, I understand they need to be there. But really, do they have to stand right in front of me every time there’s a big play? There’s a funny Facebook page dedicated to this, and if you’ve ever shot sports, you’ll get a big laugh out of it. Even if you don’t shoot sports, you’ll chuckle.

So what can you do? One way to minimize many of these problems is to get higher. But then you end up shooting down on people, which means fewer faces. With basketball, though, that’s less of a problem, since much of the action involves players looking up. Which is why photographers sometimes go up to the ceiling.

Up to the catwalks in Allen Fieldhouse is where photographers go if they want to set up a remote camera shooting down into the action. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

At Allen Fieldhouse, where Kansas plays, there are rafters in the ceiling that hold everything from lights to speakers to the scoreboard. And that means catwalks up there to provide access to them. When Charlie was assigned a recent KU game, he decided to call their sports department to see if he could get permission to go up there. His plan was to mount a camera shooting down at the basket, and trigger it with a radio remote from his courtside position. And that’s just what he did.

If you ever get a chance to do something like this, there’s one rule that’s more important than any other – you can’t drop ANYTHING! And it helps to not be bothered by heights. Charlie climbed up there (literally – a metal ladder is how you access the catwalks) with a bag of gear and one camera (Canon Mark IV) with a 70-200mm f/2.8 Canon lens. Aside from that gear, there are two accessories that make this possible. The clamp (or clamps) and the remote.

Charlie attached one Magic Arm to the lens, and a second (not mounted yet) to the body of the camera. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

For years now Bogen (now Manfrotto) has made the most popular tool for mounting cameras – the Magic Arm. Hard to describe, it’s a two-section device with a joint at the elbow, and also one at each end as well. There’s one knob that loosens and tightens all three joints at the same time, making a nearly infinite number of adjustments possible. While it would have been possible to mount the camera with just one, Charlie used two for more stability (and safety).

The radio remote is the other key, and it’s a brand that once again is widely used by photographers – PocketWizard. They make a number of different transmitters, receivers and transceivers (can both transmit and receive). The concept is simple – you connect one to the camera and use a second to trigger it.

Once up there, Charlie first picked the spot he’d like to have the camera shoot from. Next he had to make sure it was possible to clamp the camera and lens to something solid at that spot. Once that was taken care of, he used a set of safety cables to make sure that should the clamps fail for any reason, the cables would prevent anything from falling. Finally, he adjusted focus and exposure (both manually, and taped the focus ring so it wouldn’t shift), and tested the remote to make sure it was triggering the camera. It’s also important when doing this to set the camera so it won’t go to sleep. If that happens, you won’t get many pictures.

Charlie makes sure the remote is turned on and set to the correct channel before connecting it to the camera. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Because his overhead remote was trained on just the one basket, he attached the trigger (another PocketWizard) to the camera he was shooting action around that same basket with. That meant that every time he triggered that camera, the camera above would shoot too. Of course, he’ll then have a lot of useless frames (of action away from the goal), but with digital, as long as he’s got a large enough card in the camera, that’s not a problem.

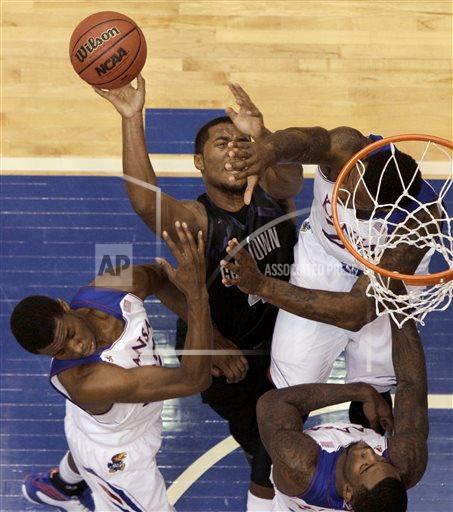

Since this was a day game, Charlie simply waited until after the game to go back up and retrieve the camera gear and photos. If it was later in the day (meaning a tighter deadline to transmit the photos), he would have also connected a WiFi device to the camera. That would let him access the photos from below, without having to go to the camera. Of the about 1000 images shot on that camera, Charlie chose just six to transmit. Click here to see one of the shots he got from that camera.

While there were probably a dozen photographers covering the game, Charlie was the only one to come away with photos from an overhead angle. He did what he’s really good at – and all of us should be doing – which is to wonder, “how can I shoot this differently.” I doubt many of you will have the opportunity to mount a camera in a ceiling, but there are almost always choices you can make for where to shoot from. Always think about whether you can choose a different angle – put the camera on the ground, climb up into the bleachers or use a different lens than you normally do. You might come away with something really unique, and that’s a good thing.

(If you want to see more of Charlie’s work, click here and type “Charlie Riedel” in the search box)

Great images . Would like to use a camera on the gym floor . I have POCKET WIZARDS , a Canon 24 – 70 lens , and a Canon 1-d-x MK-2 body . What (F-STOP ) and SHUTTER SPEED should I use sitting just back of the end line of the court ? Thanks and cont’d success in your great images .

Hi Gerry. Generally, you’ll want at least f/2.8 and 1/1000 and focused on the area under the basket. If you have enough light, then maybe go to f/4, or raise the shutter speed slightly (not higher than 1/1600). But 1/1000 should work well with 24mm (wider, more distance, can get away with a little slower shutter speed). I’d recommend NOT mounting the Wizard on the hot shoe, where it could be broken off if a player comes flying off the floor. Good luck!