In the days of film, we shot low ASA’s to minimize grain. With digital, we learned that raising ISO (the term that replaced ASA) resulted in more visible noise and loss of color saturation, so we stayed away from that too. But with today’s cameras, sensors and processing, it’s time to re-think that habit.

A few years ago Jay Maisel, a world-class photographer in New York City, was asked why he’d shot some photos at high ISOs. After all, that meant there’d be noise. His answer? “I’d rather have noise than blurry pictures.” And that’s what it often comes down to. How many good pictures have you lost because of blur, from too low a shutter speed? Taking a new approach to ISO will mean fewer lost pictures. That’s a worthy goal.

I shot this in 1979, and was using Kodak Tri-X film, which had a rating of 400 ASA. I then “pushed” it to 1600 by leaving it in the developer longer. As a larger image, it wouldn’t be acceptable by today’s standards because of the grain. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Let’s start by understanding what noise is and what causes it. Every digital camera has a sensor, and that sensor will give you the best quality at the camera’s lowest ISO. Today that’s usually around 100. When you raise the ISO above that, you’re not increasing the sensitivity of the sensor – despite what people say, that’s simply not possible. What is possible, though, is amplifying the light that the sensor has recorded. That’s what raising ISO does. It’s like turning up the volume on a radio. You can make it louder, but with a resulting loss in fidelity. That loss of fidelity in a digital camera results in a grainy, or chunky appearance, which is “noise.” Plus there’s a loss of color information too, so less saturated colors. But there are two more things that play a large role in how bad that noise might be – the size of the pixels and the processing of the information.

This is from a state-of-the-art camera in 2009, at 25,600 ISO. Viewed at 100%, the noise is very visible, but there’s still good detail. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

While many people think the number of pixels is most important, it’s actually the size of the pixels that matters more. Larger pixels mean more light-gathering capability, and thus less noise. That’s one of the reasons most top-of-the-line cameras have fewer pixels than less expensive cameras. For instance, the Nikon D5 is a 21-megapixel $6500 camera, while the 24-megapixel Nikon D3300 is only $550 (and that includes a lens!). Plus, that D5 uses an FX (“full-frame”) sensor, while the D3300 uses a smaller DX. This means not only is Nikon using fewer pixels in their most expensive camera, but those pixels can be even bigger because they’re spread over a larger area. Of course, that D5 has a lot more features than the D3300, but those larger, fewer pixels means you can shoot the D5 at absurdly high ISOs and still get great looking pictures. That’s one reason pro sports photographers use those high-end cameras, even though they’re lower resolution than other, less expensive cameras. And that’s also why small cameras, and smartphones, do a poor job in low light. They have small sensors with even smaller pixels.

As important, each new generation of cameras bring more advanced, better processing of the information those pixels record. That improved processing can mean higher quality images at higher ISOs. And that’s why a new camera with more pixels (albeit smaller ones), like the Nikon D7200 (24MP), can do a better job at high ISOs than a lower-resolution, but older model, like the D7000 (16MP). The D500, a couple of years newer than the D7200, while nearly the same resolution and also a DX sensor, is better than the D7200 at equivalent high ISOs. Which is thanks to the camera’s newer processing hardware and software.

Nikon’s Auto ISO menu lets you choose the ISO you’d like to be at (200 in this case), and then set limits for how high you’re willing to let the camera go (4000 here) to maintain a minimum shutter speed of 1/1600 second. These are the settings I used in Africa. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

What all this means is that if you’ve not changed how you use ISO, you’re missing pictures. And new features, like Auto ISO, have made that even easier. As instituted by Nikon (and I think most manufacturers offer something similar), I can set the ISO I’d prefer to shoot at, then tell the camera to automatically raise that ISO to a certain point (which I can also set), if the shutter were to drop below a certain speed. For instance, I could set the camera to 200 ISO, but let it go as high as 4000 ISO to maintain a shutter speed of 1/1000. I’ve used it occasionally in the past, mostly when shooting sports in changing light, but with my new mantra of “raise the ISO!,” I’ve decided to use it more regularly. I had the perfect opportunity to do that this past summer.

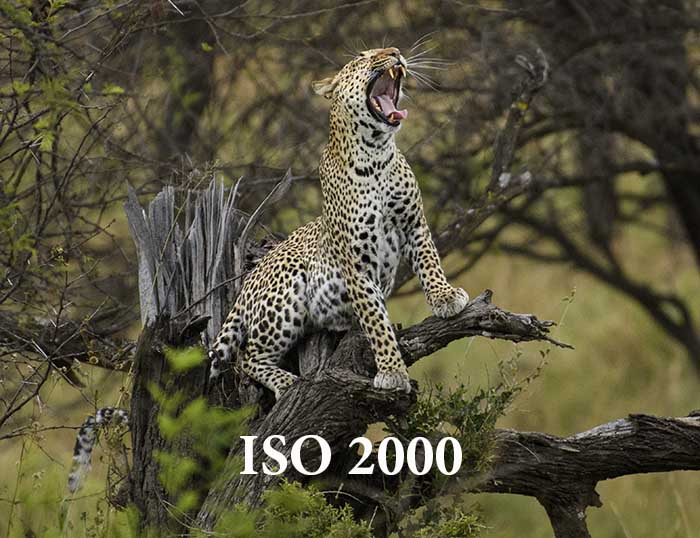

In June I led another photo safari to Tanzania and the Serengeti (and will again in 2017). When possible, I try to take new cameras and lenses and test them on these trips. This time they were the new Nikon D500 and Nikkor 200-500mm f/5.6 lens. After some quick checking at home, I found I was comfortable with the noise level up to ISO 4000. Which made that my high limit. My low would be 200, because if there’s plenty of light, that’s where I’d like to be. And for shutter speed, most of the time I went with a minimum of 1/1600. Why so high? Two reasons – long telephoto lens and movement.

Telephoto lenses magnify things. Not just the good (the subject), but the bad too. In this case the bad was movement. Standing in a truck with three other photographers and a driver, on the plains where it’s often windy, you’re on a wobbly platform. Which means you need a high shutter speed to help counter that. Add in the magnification of the telephoto, and that’s even more important. Thus the 1/1600 shutter speed decision.

How did it work out? Wonderfully. As conditions changed, I didn’t have to constantly adjust my ISO, yet was still able to keep a high enough shutter speed to make the pictures. Using Aperture Priority, I kept the aperture of the 200-500 wide open at f/5.6, so the ISO could shift up and down to maintain at least that 1/1600 shutter speed. And, with the new D500, the noise was acceptable throughout the range.

On the last morning of the safari, driving to the airstrip in the Serengeti, we found a Cheetah near the road. In shadow, the ISO has to go to 4000 to this case I set the shutter speed limit at 1/1000, as we were in subdued light. Nikon D500, Aperture Priority, white balance of Sunny, ISO 4000, 1/1000 at f/5.6, EV 0.0, Nikkor 200-500mm f/5.6 lens at 500mm.

Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

To look at true sharpness and noise, you need to magnify your image to 100% (one pixel in the image is then being shown by one pixel on screen). And here you can see that even at 4000 ISO, the noise is very acceptable. That would have been impossible even a few years ago with a DX camera. Nikon D500, Aperture Priority, white balance of Sunny, ISO 4000, 1/1000 at f/5.6, EV 0.0, Nikkor 200-500mm f/5.6 lens at 500mm.

Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

I’ve continued using it since I returned. We’ve been dog-sitting our niece’s German Shepherd puppy, and he and our dog have been playing in the backyard. Which for me is a good opportunity to shoot action. Again, I used Auto ISO, setting it to maintain a high shutter speed by letting the ISO go up. And again, it’s helped me make more good pictures.

To freeze Pringles, at right, in mid-air, I needed a high shutter speed. But the dogs were running in and out of sunshine, so I used Auto ISO to make sure I got at least 1/1250 second shutter speed when they were in the shade. Nikon D7200, Aperture Priority, white balance of Sunny, ISO 1250, 1/1250 at f/5.6, EV 0.0, Nikkor 18-140mm f/3.5-5.6 lens at 30mm.

Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Does this mean I’ll use it all the time? No. I’m a big fan of controlling what the camera does, so I’d rather choose an ISO based on what I’m doing. When shooting in fixed light, using flash or doing landscape photography, I’ve got the time to pick the right ISO for the scene. Plus, there are times where Auto ISO will actually keep you from making the picture you want. For instance, if you’re trying to create blur, Auto ISO will fight you. You’ll be trying to make the camera use a slower shutter speed, usually with a combination of low ISO and small aperture (like f/16 or f/22). If Auto ISO is turned on, it will keep forcing the ISO up to prevent that low shutter speed. Which can be incredibly frustrating until you figure out what’s happening. Trust me, I’ve been there.

Here’s the bottom line: if you’re always trying to stay at low ISOs, and missing photos because of that, you don’t need to any more. Experiment with higher ISOs to see how far you can push them before noise becomes a problem. How high is that? It’s subjective, based on personal perception, as well as the light you’re shooting in and how the images are being viewed. Finally, keep an eye out for new features, like Auto ISO, that can make a difference. Two of the biggest improvements I look for in new cameras today are high-ISO performance and cutting edge features. New models should deliver on both of these, and both will make you a better photographer.

(If you like this story, please share it with your friends, and also let them know about the links about photography I post on my business Facebook page)