In case you missed the hoopla, we were treated to a “Super Moon” on July 12. But never fear, you’re going to have another chance to see one, or better yet, shoot it on August 10.

A Super Moon is when the moon is full at the same time it’s closest to the earth. It looks bigger than usual and is great to photograph, but there are a few things you should know first.

The moon and sun are challenging to photograph, because they’re so bright. That brings up something we photographers refer to as “dynamic range of light.” Put simply, that means the range between the darkest part of a scene and the brightest. Cameras are only able to record a certain “range” of light, which is less than what we can see with our eyes. For instance, if you’re in a room with the lights off and it’s sunny outside, you don’t have any trouble seeing detail inside the room as well as outside the windows. A camera can’t do that. It can be set to record the scene inside, but then the windows will be overexposed, appearing in the picture as big rectangles of white. Or you could choose to expose for the outside light, in which case the inside area would be underexposed, or mostly black. That’s one of the challenges of photographing the sun or moon. They tend to be much brighter than the areas around them. But there’s a way around that, and it too involves range of light.

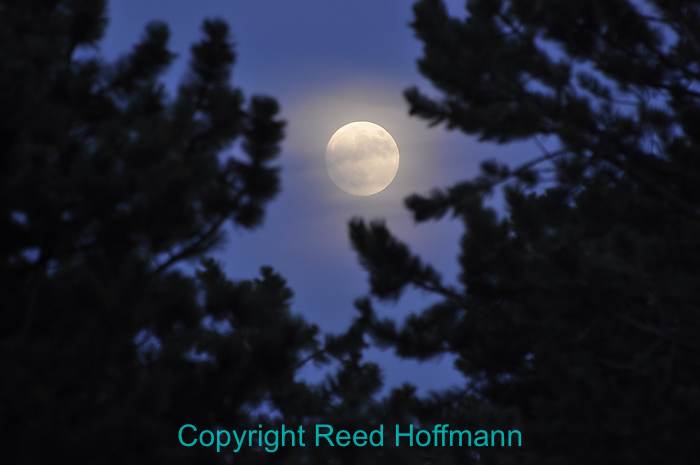

The sky was still too bright for this shot, so the moon looks washed out.

Nikon D5300, Aperture Priority, ISO 400, 1/1250 at f/5.6, EV -1.0, 80-400mm lens at 400mm. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Think about how the moon looks when you see it during the daytime. Kind of faded, because there’s so much light around you. At dawn and dusk the moon will be much brighter, but there’s light around you so you can still see other stuff too. It’s a similar situation with the sun. When it’s fully up in the sky it’s so much brighter than everything else that you’d hurt your eyes trying to look at it. But when there are clouds in front of it, or it’s low in the sky with more atmosphere between us, it’s dimmed in intensity. That’s the secret to photographing either of them – when the range of light is at a point that you can expose for both them and the surrounding area. Let’s get back to that Super Moon.

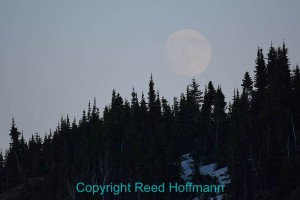

If you properly expose for the moon full lit at night, that’s all you’ll see. Nikon D5000, Aperture Priority, ISO 400, 1/640 at f/5.6, EV -3.0, 70-300mm lens at 270. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

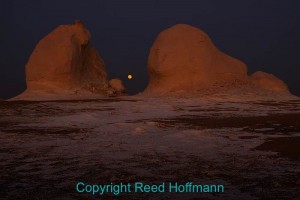

There was just enough light left to show these rock formations in the White Desert of Egypt, though I had to raise the ISO.

Nikon D700, Aperture Priority, ISO 800, 1/125 at f/4, EV -1.7, 24-70mm lens at 38mm. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

If it’s nighttime and you’re exposing for the moon (so you can see detail in it, like the craters), then all you’ll get is the moon. Kind of boring. The secret to photographing the moon is to NOT do it at night, and to include more than just the moon. Instead try photographing it early or late in the day, when there’s enough available light that you can make a good exposure of the moon and include another subject in the photo.

I couldn’t pass up this shot, asking Rachel to scramble up the rocks to give me a subject with the moon at sunset in Rocky Mountain National Park. Nikon D5000, ISO 200, 1/500 at f/9, 70-300mm lens at 180mm. Copyright Reed Hoffmann.

“So Reed,” you’re thinking now, “what you’re saying is the best pictures of the moon aren’t at night, and aren’t of just the moon?” Exactly! The moon is just part of the picture. And if you think of photos you’ve seen that include the moon, you’ll realize that’s always the case.

To do that then, it helps if you know when the moon is rising and setting, and where. You can find that on the internet, but better yet are smartphone apps that will show you, based on where you are. With that information at hand, you can look for a foreground subject that will go well with the moon, like a person, mountain, horse on a ridgeline or something else cool. A telephoto lens (at least 200-300mm) will help keep that Super Moon looking super. But nice pictures can be made with wide-angles too, it’s just the moon won’t look so super then.

With daylight, exposure shouldn’t be much of a problem. If your shutter speed is getting down around 1/100 or lower, a tripod can help. If you don’t have a tripod, brace the camera against a pole, tree, railing or whatever’s handy. For white balance I generally start at the sunlight setting, but since I’m shooting RAW files, I can always adjust the color balance afterward.

So now you’ve got your assignment – go shoot that Super Moon! And if you miss it on August 10, don’t feel too bad. There’s another one just around the corner, on Sept. 9.