One of the unique “gifts” of photography is its ability to stop time. We can freeze a moment and study it, which we can’t do with our eyes alone. Athletes in the air, a baseball coming off a bat, dogs in mid-bark are all photos we love to look at for that reason. And while most people think shutter speed when they think of stopping action, there’s actually something faster – flash.

In the early days of flash photography, flash powder, and then flash bulbs, would burn to their full intensity and then fade out. That meant that the timing of when the shutter opened wasn’t very critical. If it was a little early or late in the duration of that burn, you still got a picture, because the burn was slow. Electronic flash changed that. To understand why, you need a little background on flash and shutters.

This is what happens if you shoot at a higher flash sync speed than the camera can use, which results in a black bar. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

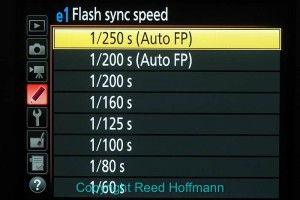

Electronic flash is a brief pulse of light. That means the timing of the shutter must be very precise – it has to be open at exactly the right moment. That’s a pretty neat trick to achieve, since there are two shutter curtains in most cameras, one opening the sensor to light, the other closing. Of course, that means both curtains must be clear of the sensor when the flash goes off. At slow shutter speeds that’s easy. But at higher shutter speeds, there’s a risk that second curtain could start coming up before the first has cleared the area. If that happened, you’d get a black bar across one side of you photo. That’s why most cameras have a maximum “sync” speed, which is the highest shutter speed the camera can achieve before getting that black bar. That shutter speed is around 1/200 or 1/250 second.

If you know much about shutter speed, then you realize that even 1/250 second is not very fast. At least not if you’re talking about stopping action. Most fast-action photos, where the intent is to freeze the action, are shot at 1/1000 second or higher (some of our cameras today can shoot at up to 1/8000 second). So if flash is capable of stopping action, then how does that work if you can’t use a shutter speed higher than 1/250? There are two answers: one involves a lack of light, and the other lies in the shortness of that pulse of light.

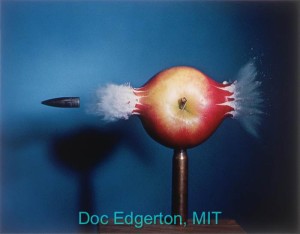

Harold Edgerton is best known for his work with stroboscopic lights, creating photos like this. MIT Photo.

By now everyone’s seen photos of bullets going through balloons or other objects. Harold Edgerton is best known for that. Those photos are actually made using a very long shutter speed – as much as a second or more. That’s because there’s no light on in the room. Remember, the ley to taking a picture with flash is that the shutter is open when the flash fires. If the room is dark, you can leave the shutter open, simply waiting for the flash to light the subject. The duration of the flash is what then determines exposure. And as I said before, electronic flash is a brief pulse of light. A very brief pulse. So short, in fact, that with the right flash, you can freeze a bullet in mid-air. Remember, light travels at 256,000 miles per second. That’s faster than a speeding bullet. So with the right flash, a dark room and good timing, you can photograph a bullet.

Pringles isn’t as fast as a bullet, but can still be caught mid-leap by the short pulse of flash. If the room were brighter there might have been a chance of blur with this shutter speed of 1/60 second, but since there’s so little available light, the flash is the only real source of illumination. Nikon D7100, ISO of 400, shutter speed of 1/60 at f/6.3. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

The flashes we use with our cameras today aren’t fast enough to stop that bullet. But they are fast enough to stop other types of action. How fast they are is a question of their power output. For instance, Nikon’s SB-700 speedlight is capable of a burst as short as 1/40,000 of a second. But that’s at its lowest power setting, 1/128 power. At full power it fires at 1/1042/sec. At 1/4 power, 1/2857. At 1/8, 1/5714. What’s important to see here is that the less power the flash uses, the shorter the duration of that flash. But I already told you that maximum sync speed on most cameras is somewhere around 1/250 second. So how does that shorter flash sync help you stop action? By firing repeatedly.

At higher shutter speeds (above sync), there’s actually a strip of light exposing the sensor as the two shutter curtains travel across it. With a constant light source, like sunshine, that’s no problem. If there’s just one brief pulse of light, though, portions of the frame would be black (as mentioned above). But what if you could pulse the light so fast that it’s literally “painting” the subject with light while that strip is crossing the sensor? That’s what “high-sync” (what Nikon calls Auto FP) does. If you turn that on in your camera (under the “Flash Sync speed” menu on certain Nikon cameras), then as long as you’re using a compatible flash (like one of Nikon’s many accessory speedlights), will do that. With Nikon cameras, you’ll find that some of offer Auto FP at 1/200, 1/250 or even 1/320. Of course, it only needs to pulse the that at shutter speeds above the maximum sync (either 1/200, 1/250 or 1/320). If you drop your shutter speed to sync speed, or below that, the speedlight reverts to standard behavior and just pushes out one burst of light.

In this case I combined a high shutter speed with flash to freeze this biker flying down the hill. If I’d shot at a slower shutter speed, there’d be blur from the available light. Nikon D750, ISO 100, 1/1000 at f/5.6, EV -1.0. Photo copyright Reed Hoffmann.

Finally, you need to remember that if it’s pulsing light, firing multiple bursts in quick succession, it won’t be able to deliver the power it could with one burst. So at high enough shutter speeds, smaller apertures and/or further from your subject, your photos could start to look underexposed. That’s because the speedlight simply can’t put out enough power, pulsing, to properly illuminate the subject. In that case you need to make an exposure adjustment, like raising ISO, opening the aperture or moving the flash closer to the subject.

Once you understand this, and turn on Auto FP (if your camera has that option), then your accessory speedlight is capable of much more than just adding light. It can freeze action, and now you have a new technique you can use to make different pictures. And as I always say, in photography, different is good.