In photography, f/4 is f/4 is f/4, right? Whether you’re changing lenses, zooming the same lens or comparing exposures with a friend using a different make of lens, f/4 is f/4. The answer is actually, “sometimes yes, sometimes no,” and the reason why is well worth knowing.

I shoot both mirrored and mirrorless Nikon cameras, and about a year ago I added the Nikon 14-30mm f/4 S lens to use on my mirrorless bodies. Shortly after that, while teaching night photography during one of my workshops, I noticed something – that new 14-30mm f/4 lens seemed to be giving me brighter exposures than expected. Which didn’t make sense. Switching from the F/2.8 lens I was using to this f/4 lens means I should need to double either my ISO or exposure time to make up for the loss of that full stop. But I didn’t. Instead, perhaps a half-stop change was all that was needed. I thought, “hmmm, maybe it’s something with the larger mount on the Z cameras or the shorter distance to the sensor,” and I moved on with life. But it kept nagging at me, because f/4 should be f/4. It was, but I wasn’t going far enough in my thinking.

In the past, my usual lenses for night photography were Nikon’s 24-70mm f/2.8 (on the left) and their 20mm f/1.8 (on the right). Now, though, the 14-30mm f/4 S lens (center) has become a welcome member of that group, and not just for its wider field of view.

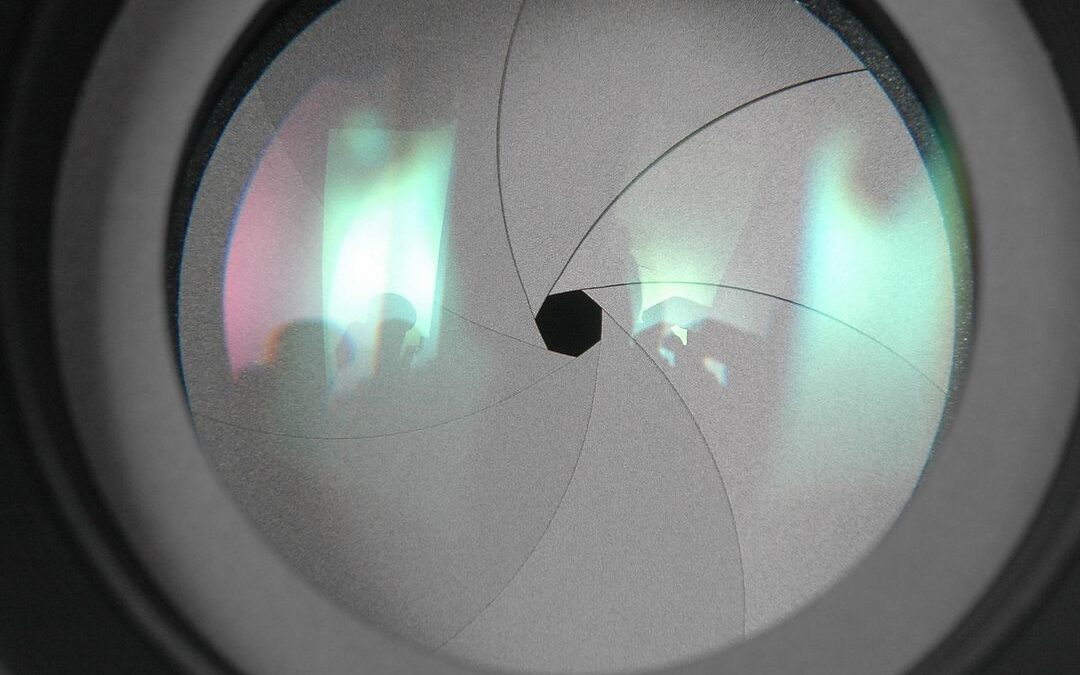

The F-stop of a lens is a mathematical calculation determined by the focal length of the lens divided by the physical size of the aperture inside it. That’s why a 200mm lens with an aperture size of 50mm is an f/4 lens. A 50mm lens with a 25mm aperture is also an f/4 lens, However, the number of elements, the distance between them and the coatings used are probably different from that 200mm lens. Those three things all affect “light transmission,” which makes sense. No matter how good the glass is inside a lens, there will be some light loss from when it enters to when it exits and strikes the sensor. Remember, F-stops aren’t so much calculations of quantity of light as they are a simple measurement. So if those other factors are different, the amount of light will probably be different too. For still photograpers, that’s rarely a problem. While there may be a slight change in exposure when zooming or changing lenses, it’s unlikely to create any serious issues. For filmmakers though, this is a problem.

In the past, to make a picture like this, I would have needed around 4000 ISO at f/4 and 30-seconds to keep the starry night sky clearly visible. With the better light transmission of the Nikon 14-30mm S lens, I’m now able to create this at just 2000 ISO. For night photography this is especially important for two reasons: one, lower ISOs mean less noise. Or two, a shorter exposure time could be used help reduce possible blur in the stars. Nikon Z 6, Manual exposure, 3800K white balance, ISO 2500, 30-seconds at f/4, Nikkor Z 14-30mm f/4 S lens at 19mm.

Sudden changes in exposure in a video or film, without any changes in the light itself, are pretty noticeable. That’s why filmmakers rely not on F-stops, but T-stops, because they care about “Transmission.” T-stops indicate the quantity of light, not a focal length/aperture calculation. As they zoom a lens or change lenses for different shots in the same environment, they want to make sure that transmission value is the same. Thus T-stops. Once I understood that, I knew what to look for to help me understand my 14-30mm f/4 S lens. I found that at DXOMark. According to their testing, this lens has better than normal light transmission, letting in more light than many other lenses at that aperture.

In this moonlit scene at Dead Horse Point State Park in Utah, notice the tremendous amount of detail I can get with a relatively low ISO. Nikon Z 6, Manual exposure, Sunny white balance, ISO 2000, 30-seconds at f/4.5, Nikkor AF Zoom 14-30mm f/4 lens at 16mm.

So the next time you change lenses – or zoom – and notice a slight shift in the exposure despite all exposure settings remaining the same, you can understand why. And the next time I suggest an exposure for a student during a night shoot, I’ll understand why their result may look different than mine, if they’re using a different lens. Pretty fascinating, right?

F-stops and T-stops are different, both important, and both can affect your work, providing you understand what they mean. And this is one of the many reasons I continue to love photography. If you’re willing, there’s always more to learn.

(If you like this story, please share it with your friends and let them know about the links on photography that I post on my business Facebook page. I’m also on Instagram and Twitter, @reedhoffmann. And if you’re curious about the workshops I teach, you can find them here. And, you can subscribe to this blog on my home page.)

Beautiful and mysterious night shot of the barn and leaning tower/structure with the wonderful night sky. Thanks for sharing our love of teaching and love of photography.

Alan

Thanks Alan. That structure is an old windmill with its blades blown off, won’t be standing much longer I’d guess.