If you’re serious about photography, then odds are you’ve either heard people say you should shoot RAW. In fact, there’s a pretty funny scene in Adorama’s 2016 Top Photographer series (at the 7:34 mark in this link) where one competitor has to admit she forgot to set her camera to RAW and shot JPEG instead. The host looks like he’s about to faint, and you’d think they were going to kick her off the show right then and there. But you know what? Her photo, JPEG and all, won that day’s judging. Because it was the best PICTURE, regardless of format. Yes, it’s a fact that RAW gives you more flexibility when editing photos, but does that mean JPEG is bad? No, and that’s why I’ve been shooting mostly JPEG lately. But before I go into why, let’s make sure we’re on the same page about what JPEG and RAW mean.

When any digital device captures an image, it’s actually recording light striking a sensor and then doing one of two things: either processing that data into an image immediately, or just saving the RAW data to the card. By default, most devices process the image, creating an picture that can be viewed and used right away. That process results in a finished image file, a TIFF, which can be quite large (about three times, in megabytes, what the megapixel count is). Because early digital devices had very limited storage, the only way to make digital captures feasible at that time was to compress that TIFF into a JPEG before saving to memory (and then automatically deleting the TIFF). JPEG was created as a universally accepted method of compressing digital images, and while cameras used to also offer the capability to save images as TIFFs (as well as JPEGs or RAW files), few now do.

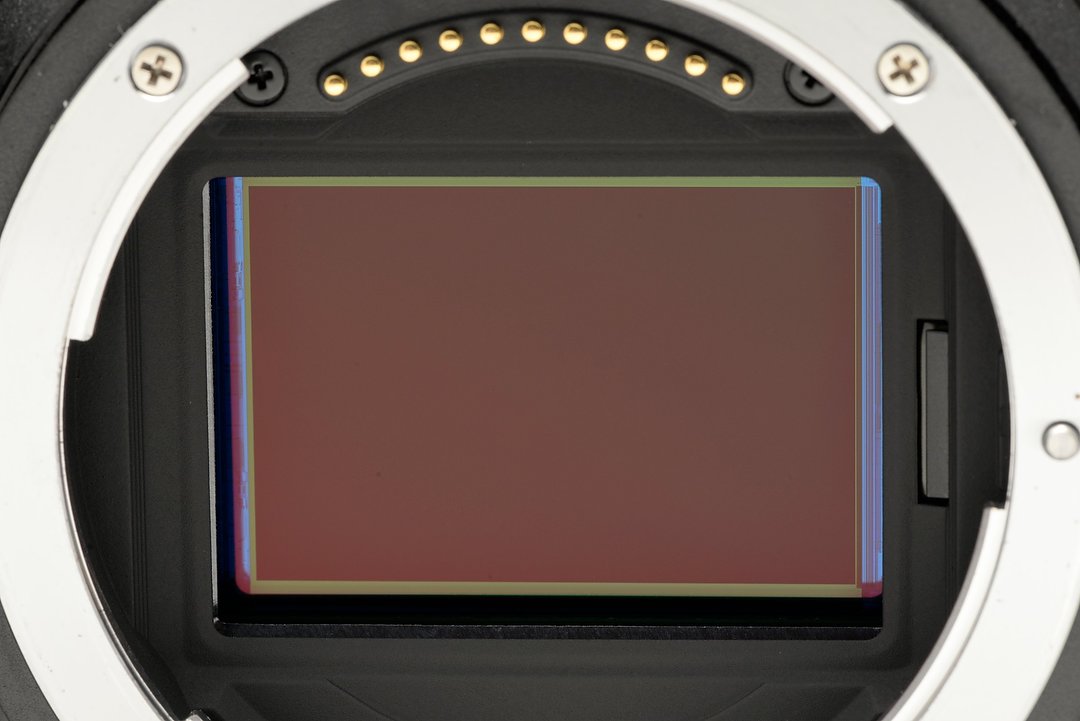

Your camera’s sensor simply records light. You choose whether it processes that information into a JPEG, or simply saves it as RAW data.

When you open a JPEG in editing software, it’s then decompressed back into a TIFF. That once smaller JPEG file is now a much larger TIFF (same resolution, but bigger file), much like inflating a balloon. If you then make any changes to that image, such as cropping, adjusting color, contrast, etc., you need to save it again, either as a large TIFF file or as a new JPEG (which adds another step of compression). While JPEG is universally accepted, there are also some newer compressed formats, like the HEIC file today’s iPhones generate. However, the end result is essentially the same – a compressed image that takes up less space. And all devices begin that process by capturing RAW data off the sensor, though not all of them have the ability to save that information. Some, however, can save that RAW data.

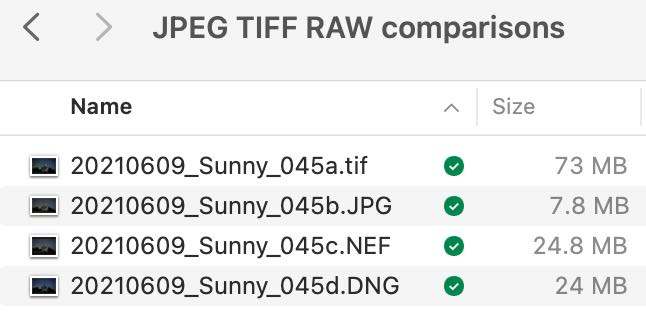

Here’s a good example of the size differences depending on format, from my Nikon Z 6 (a 24-megapixel camera). If it wrote a TIFF to the card, that would take up 73MB of space. A high-quality (low compression) JPEG, on the other hand, only 7.8MB. If I choose to have it write a RAW file instead (what Nikon calls a “NEF”), that’s about 24MB. And after I edit that NEF in Adobe Camera RAW, I save it as a DNG, which remains about 24MB. That DNG gives me the ability to do non-destructive editing.

Pretty much every digital camera – and even some smartphones – let you set them to save that RAW data, either in addition to a JPEG or as the only file. Remember, RAW data is not a photo yet because it’s just 1’s and 0’s that haven’t been processed to create a photo. Most people don’t realize it, but that’s why most RAW formats also include a highly compressed JPEG inside the RAW file. That’s so the camera can provide an instant preview of the photo on the LCD (instead of having to process RAW data in-camera on the fly). That unprocessed data is what makes RAW photos special, and it gives RAW files some advantages over JPEGs. Why?

First, JPEG, by its very nature, means some image information is lost through compression. Does that mean a loss of image quality? Yes. However, if you set your camera for best quality JPEG (meaning a larger file but less compression), it’s rare that you’d see any issues from that. One thing to keep in mind when editing JPEG photos, though, is to avoid doing multiple “Saves” of the same image. Remember that each time you save a JPEG, you’re compressing it all over again. Doing that a couple of times is generally not a problem, but if you want to edit a JPEG photo again after an initial edit, it’s better to start over with the original JPEG. That’s why you want an editing workflow where you never save over those original JPEG files. If you shoot JPEG, always do a “Save as” when editing photos, so you can go back to the original JPEG the camera created. (Note: much of today’s editing software is smart enough to help you avoid overwriting the original JPEG by essentially hiding it from you and only generating copies created from it.)

Secondly, since JPEG is a processed image file, you want to be careful with your exposure and white balance before taking photos. Those could be considered “baked in,” and while you can adjust them later, you’re limited in how far. Plus, any adjustment means a loss of image data. This is where starting with a RAW file has its biggest advantage.

I do all of my night shoots in RAW format because I have so little control over the scene. For instance, I didn’t expect a lightning bug to fly through my frame while photographing this old schoolhouse. Having that RAW data meant I had more ability to push and pull both color and exposure, to help me get the most out of my photo. Nikon Z 6 II, Manual exposure, 3800K white balance, ISO 3200, 30 at f/2.8, Nikkor Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S lens at 24mm.

As I said above, setting your camera to capture RAW files means having that camera write numbers to the card, not a photo. Those numbers then have to be decoded (“demosaiced”) into an image file. While that RAW file will be larger than a JPEG (but still smaller than a TIFF), the fact that it’s unprocessed means you have much more flexibility when you edit it. ISO, shutter speed, aperture and focus are fixed. But color, contrast, sharpening, noise reduction, etc. – in other words, much of what makes up a photo – can be shifted after capture, in editing software, without a loss of quality. Of all those things, white balance (color) and more exposure latitude (darker or lighter) offer the greatest advantages for most of us.

Since a RAW file has not had its color processed (decoded from those 1’s and 0’s), you could shoot with the camera at any white balance setting and change it later, in software, to any other white balance without any loss of image quality. With a JPEG file, since it’s already been processed into a finished photo in-camera, you have less ability to shift color, and that shifting comes with a loss of image data (and possibly a noticeable visual loss as well).

The additional data a RAW file contains (remember, it’s normally larger than a JPEG) also means that you have some ability to recover overexposure. Overexposed highlights in a JPEG file are simply gone (because it’s been processed in camera), whereas a RAW file may allow you to bring back at least some of that highlight detail. That same RAW file will also allow you to bring out more shadow detail afterwards in editing. Doing that to a JPEG file can quickly result in those shadow areas turning blocky. So a good rule of thumb is that anytime you’re worried about getting exposure or color right in camera, shoot RAW.

This is a full-frame image from the workshop I led to Tanzania last summer. I accidentally had my camera set to +.7 exposure compensation, which resulted in an overexposed image. If this were a JPEG, I’d be in trouble, unable to recover proper detail and color in sections of the lion’s face. Luckily, I was shooting RAW. Nikon D500, Aperture Priority, Sunny white balance, ISO 400, 1/800 at f/6.3 in Matrix metering, +0.7 EV, Nikkor AF-S 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR lens at 500mm.

Since it was a RAW (NEF) file, I had the ability to bring back those overeexposed areas and save the photo.

After reading this far, you should now understand the main advantages that RAW files offer over JPEGs. Does that mean you should always be shooting RAW? Not necessarily.

As I mentioned, RAW files are larger than JPEGs, so if space – either on cards or hard drives – is an issue, that’s a consideration. Also, larger files mean more time needed to download them. If you’re in a hurry, or on a tight deadline, that can be an issue as well. RAW files also require a more powerful computer to edit them quickly as opposed to JPEGs, and longer to save. These are among the reasons most wire services (like the Associated Press and Getty Images) have their photographers shoot JPEG almost all the time. Does that mean they’re making poor quality images? No, not if they’re careful with exposure and white balance. Since those staffers are very experienced photographers, they all know how to do that.

Covering the Big 12 Women’s Tournament this month for the Associated Press, I shot JPEG. Having fixed lighting, I was able to dial in my exposure and create a custom white balance beforehand, which allowed me to shoot JPEG and have a very fast workflow. That helped me edit, caption and transmit 6-8 photos during halftime of each game, and another twenty or so right after it ended. I also shot KU and K-State basketball for the AP earlier this year, again as JPEG (one of those photos is at the top of this story). Nikon Z 9, Manual exposure, Preset white balance, ISO 4000, 1/2000 at f/2.8 with a Nikkor 300mm f/2.8 lens.

As for me, remember at the beginning of this story where I mentioned I’ve been shooting JPEG a lot lately? Any time a new camera comes out, the manufacturer releases an update to their own software (usually free) that same day that’s optimized for opening RAW files from that camera (each new model of camera – even from the same manufacturer – outputs a slightly different “flavor” of RAW file than the other models). But most photographers prefer using third-party software that they pay for, as it’s often faster and more workflow-friendly (like Adobe, Capture One and others).

However, before those company’s software can read those new RAW files, they have to acquire a wide variety of files from that camera, re-write their software to do a good job decoding them and then push out updates. All of that takes time. Since I have a new camera, the Nikon Z 9, I’m currently waiting for Adobe to get a finished update out so I can use their software (Adobe does have a beta version out now, but I’m not happy with its results. Nikon’s free NX Studio, of course, handles the files beautifully, but is slow). So while I wait for Adobe, what do I do in the meantime? Mostly, I shoot JPEG.

Juvenile (above) and adult bald eagles having a mid-air tussle in January at Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge. Almost everything I’ve shot with my new Z 9 since receiving it in late December, inclduing this photo, has been as JPEGs. Nikon Z 9, Aperture Priority, Sunny white balance, ISO 450, 1/2000 at f/8 in Matrix metering, 0.0 EV, Nikkor AF-S 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR lens with Nikkor TC-14e III teleconverter for 700mm.

My Z 9 arrived at the end of December, so I wanted to use it to shoot the Kansas City Chiefs in their playoff games in January. I cover the home games for AP Images, shooting for commercial use. That means I’m required to shoot RAW in case a client wants to take advantage of what that RAW file offers. For immediate deadline use, though, JPEG is fine. Photographers doing this same assignment for other teams usually shoot JPEG plus RAW, which means the camera saves both types of file (either to a single card or to separate cards). Since a JPEG file can always be generated from a RAW file, and my workflow is fast even with RAW, before the playoffs I only shot RAW (no JPEG). However, since Adobe’s support for the new Z 9 isn’t where I’d like it to be yet, I shot RAW + JPEG, knowing that eventually the Adobe support would be there for those RAW files, and I’d use the camera-generated JPEGs for game-day.

JPEG of Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes under pressure from Buffalo Bills defensive end Jerry Hughes during the first half of their divisional playoff game, Sunday, Jan. 23, 2022. JPEG, from Nikon Z 9, Manual exposure, ISO 6400, 1/1600 at f/5.r, Nikkor 200-400mm f/4 lens at 360mm.

That means I’ve been shooting a lot of JPEGs (and not just the playoff games) since getting the camera. And working with those JPEG files has reminded me of just how good a lightly compressed (best quality) JPEG can be. In the early days of digital, with relatively low-resolution cameras (which created small files with little data), having a RAW file was very important. Today, though, with most cameras in the 20-megapixel range (and the Z 9 is 45-megapixels), there’s so much more data to work with, even from JPEGs, that I believe the difference in quality is less of an issue than it used to be. Yes, I’m still more limited in color and exposure adjustments, but having an electronic viewfinder that accurately shows me exactly what’s happening with color and exposure before I ever shoot the picture helps me stay on target.

Another JPEG, from some of the bird photography I was doing in February. Nikon Z 9, Manual exposure, Sunny white balance, ISO 5000, 1/3200 at f/5.6 in Matrix metering, -0.3 EV, Nikkor AF-S 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR lens.

Does this mean I’m going back to shooting JPEGs full time? No. I still want as much flexibility in editing my pictures as I can get. And while I tended not to use my previous high-resolution cameras (36 and 45-megapixel) a lot because I didn’t always need or want the resulting large files (50-60MB each), Nikon’s new “High-efficiency” RAW format in the Z 9 gives me the best of both worlds. A RAW file with more editing capability in a size (around 30MB) that’s only a few megabytes larger than the RAW files I’d get from my 21 and 24-megapixel cameras (and only about 25% larger than Z 9 JPEGs at best quality).

So yes, I’m eager to get back to shooting RAW files once Adobe’s quality is where I’d like it to be. But in the meantime I’ve had the pleasure of seeing just how good today’s JPEGs can be, and expect that going forward, in the right situations, I’ll opt to shoot JPEG more often. Photography, especially over the last 20 years, has been all about change. Which means Photographers should always be willing to question how they’re doing things, and be willing to change. Change, after all, is one of the best ways to continue growing creatively.

(If you like this story, please share it with your friends and let them know about the links on photography that I post on my business Facebook page. I’m also on Instagram and Twitter, @reedhoffmann. And if you’re curious about the workshops I teach, you can find them here. And, you can subscribe to this blog on my home page.)

Good stuff, Reed. Confirms what I’ve been telling myself for a while.

Must reading for all photographers … students, newbies, and experienced pros alike.

Hello Reed,

How many of these shots did you use an FTZ and F Mount lenses?

Hi Terry. I’ve used my FTZ converters with all of my F-mount lenses for the last couple of years with no issues. In this story, the ladies diving for the basketball, the eagles fighting, Mahomes about to pass and the Cardinals in mid-air were all taken with F-mount lenses and the FTZ converter. That’s one of the reasons I’ve never considered leaving Nikon, I love the glass I’ve got, and own a number of long, expensive lenses. And all of them have performed exceptionally well with my Z cameras, from the first Z 6 to the Z 9.

Thanks Reed!

Very interesting piece!

And the bird photographs are amazing!