If you’ve ever tried to photograph lightning during daytime, you know it’s almost impossible. By the time you press the shutter button, it’s gone. That’s why lightning triggers, while no guarantee of success, exist. But the addition of the new “Pre-release” feature in Nikon’s Z 9 cameras now make those triggers obsolete. It guarantees success, as I found out last week.

Over the last half-dozen years I’ve been running small-group photography trips to places around the U.S. Sedona, with many great locations nearby, moderate summer weather (at least by Kansas City standards!) and a good chance for storms has been high on my list of “need to do a workshop there.” Last week I finally did, and it was as good as I’d hoped (I’ll write a blog past about that in the next few weeks). But it was the thunderstorm we watched Thursday evening that resulted in a new “Aha!” moment for me.

Among the many features added to the Nikon Z 9 with the release of firmware 2.0, “Pre-release” was an eye-opener for action photographers. As I wrote in an earlier post, it allows you to wait until you see the action, then press the shutter button and capture the moments before you pressed. It really changes how you work, as I explain in this story. But it wasn’t until I was on my way to Sedona, and thinking about the possibility of lightning, that I realized I could take advantage of Pre-release for that. While we had some lightning the first night, while I was running a low-level lighting demonstration, capturing lightning during a time exposure is pretty easy. It wasn’t until a couple of days later that we had lightning during daylight. That’s a lot tougher to shoot.

This was the night shoot, with low-level lighting (using LumeCubes), that I created up for my group the first night. The storm in the distance was a bonus, but when doing 15-second exposures, capturing lightning is pretty easy. I did turn on the intervalometer feature built into my camera so it would keep firing those long exposures with only .5-second between shots. Nikon Z 9, Manual exposure, Sunny white balance, ISO 200, 15-seconds at f/5.6, Nikkor Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR lens at 54mm.

Returning to Sedona from another shoot for sunset, I took my group up to Airport Mesa, where there’s a nice overlook. Our goal was to photograph that last hour of sunlight on the mountains across from us, but a storm rolled in. While it blocked most of the sun, it also gave us a lightning show. And that’s when I turned on Pre-release. When you do that, and press halfway down on the shutter button, the camera starts recording images at 30 frames-per-second in a continuous loop to internal memory (not the card). When you see action happen, then you push the shutter completely down and the camera records that last one-second, half-second or one-third second of action from the loop onto the card (you choose the amount). In other words, it goes back in time to capture something that’s already happened. And it made photographing lightning incredibly easy.

See it, then press the shutter button and you’ll have it. That’s as complicated as it gets as long as you turn on the Pre-release feature with the Z 9. And while the lightning only lasted about a half hour, in that time I made a number of nice photos to choose from. Nikon Z 9, Aperture Priority, Sunny white balance, ISO 500, 1/60 at f/8, hand-held, in Matrix metering, -1.0 EV, Nikkor Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 VR lens at 65mm.

To do that, I kept the camera up to my eye, and each time I saw lightning pressed the shutter down fully. And each and every time I ended up with lightning pictures. Note the plural. Often I’d end up with several lightning photos from one flash, and one time I even had ten frames. So what’s the catch? I can’t shoot RAW, as the camera automatically switches to JPEG, although still with the full-resolution 45-megapixels. There’s also an option to shoot at 120 frames-per-second, although at a reduced 11-megapixels. But still, wow.

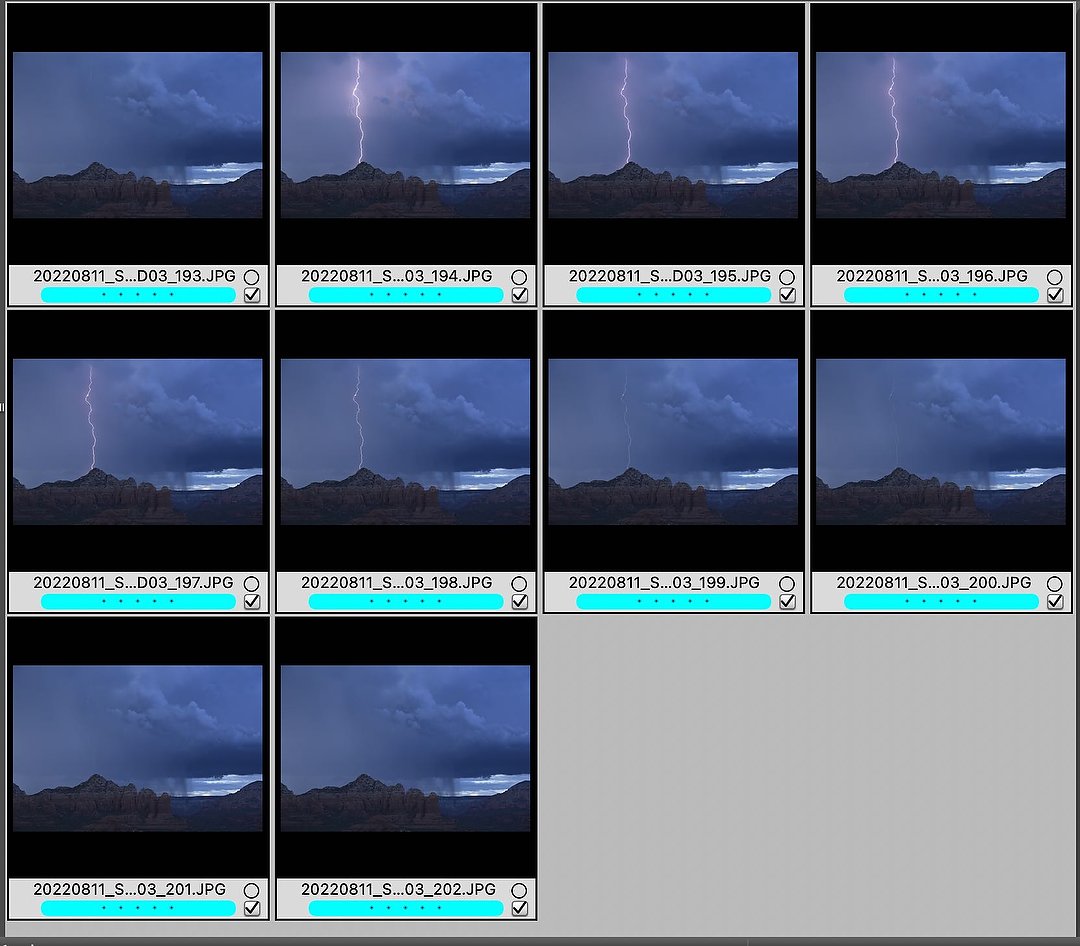

From start to finish, I can see lightning in each image of this ten-frame sequence. Which means that since the camera was shooting at 30 fps, the burst lasted for about a third of a second.

Of course, for now, lightning triggers still have a market, since there are very few cameras that can do this. But for those folks lucky enough to have a Nikon Z 9, that’s one less accessory they’ll be tempted to buy.

(If you like this story, please share it with your friends and let them know about the links on photography that I post on my business Facebook page. I’m also on Instagram and Twitter, @reedhoffmann. And if you’re curious about the workshops I teach, you can find them here. And, you can subscribe to this blog on my home page.)

Thanks very much, Reed!

Reed,

Thank you!

Absolutely awesome!