Aside from understanding what the different focus modes on your camera do, the single best thing you can do to improve your use of autofocus is what’s often referred to as “back-button focus.” Here’s why…

Back in the early 90s, when decent autofocus was in its infancy, I avoided it. Too slow. As the systems got faster and more accurate, I, along with many photographers, started to embrace it. And pretty soon we learned that it was better, and faster, than the best of us at focusing. Since then it’s gotten better and better, and the options to control autofocus have gotten more complicated. I addressed those options in another story a while back, so now I want to talk about back-button focus.

By default, every camera today initiates autofocus when you put a little pressure on the shutter button. Press halfway down, the camera focuses. Push the rest of the way down and it takes a picture. Pretty simple. My problem with that system is that it relies on one button for both focusing and shooting. If you only shoot non-moving subjects, that works okay. Of course, if you’re not going to let autofocus rule your composition, you’ll also need to get adept at shifting the active focus point. Otherwise you’ll likely end up with your subject in the center of every photo, which is not a good thing. But what if you shoot moving subjects?

In this scene, I need the leaf closest to me (lower right) to be sharp, so that’s where I need to focus. Using the traditional method, I have to hope there’s an AF sensor in just that spot, or lock focus there and re-compose. Nikon D850, ISO 400, 1/50 at f/6.3 in Matrix metering, -0.3 EV, Nikkor 18-35mm f/3.5-4.5 lens at 18mm.

Let’s say you enjoy photographing sports, wildlife, or worse yet birds in flight (very challenging!). First, of course, your camera’s AF system needs to be set to AF-C (Continuous AF, or AI Servo) so it can try to track and follow focus on a moving subject. Then you need to get the active focus point on the subject and keep it there as the subject moves, and at the same time slightly press the shutter button to tell the autofocus system to get to work. If you’re lucky, it will grab focus quickly and you can then press the shutter button down completely and take your picture. But what happens next? As you release the shutter button, you turn off autofocus. And as you press to shoot another frame, the system needs to once again acquire focus and start tracking. You see the problem here, right? Unless you’re going to keep the shutter button held down and fire continuously, the camera needs to keep re-focusing on the subject each time you press, which offers more opportunities for mistakes. Unless, of course, you’re really good at shooting without taking pressure off the shutter button between pictures. Good luck with that!

More expensive cameras usually have an AF-ON button, which does the same thing as the shutter button, unless you change how it functions.

So the problem here goes back to my complaint about having one button do two jobs. What if you could change that? Have one button that controls focus on/off, and a second that takes the picture? That’s exactly what back-button focus does. You may have noticed that most pro-level cameras have a button on the back that’s marked something like “AF-ON.” Out of the box, that does the same thing that pressing the shutter button does – initiates autofocus. “Back-button focus” is when you tell the camera to ignore the shutter button for AF and use only that button. That’s done via the menus. On the Nikons I use that have an AF-ON button, it’s in the Custom Settings – Autofocus – AF activation – AF-on only. What that really does is turn off autofocus for the shutter button. Now, the only way to get that camera to focus is by pressing that AF-ON button with your thumb. Pressing the shutter button with your index finger still turns on the meter and shoots a picture, but no longer has anything to do with AF.

What, you say your camera doesn’t have an AF-On button? No problem. Again, most cameras allow you to program one of the buttons on the back to do just that. On my Nikons without an AF-On button, there’s an AE-L/AF-L button. By default, that locks both exposure and focus if I press and hold it. But again, in the menus, I can re-program that to be an AF-ON button, just like the cameras that already have that button. Which leads us to why changing your camera to do this can be such a great thing.

Cameras that don’t have a dedicated AF-ON button can usually be modified in the menus to put that function on a button they do have. On my Nikons without an AF-On button, the AE-L AF-L button can be set to perform AF-ON. I change that in the Custom Settings – Controls.

If I’m photographing a moving subject, I frame it up, put the active AF sensor on the subject, then press and hold the AF-On button with my thumb. At that point the camera acquires focus on the subject, and as long as I keep that button pressed down with my thumb, tries to keep the subject in focus as it moves. And while it’s tracking the subject, I’m free to shoot whenever I want, by pressing the shutter button with my index finger. I’ve separated the act of focusing (thumb) from that of shooting pictures (index finger). I no longer have to worry about keeping pressure on the shutter button to keep AF active – holding my thumb down does that. But there’s another real advantage to this, and that involves non-moving subjects.

To make a photo like this, you need to make sure your camera is set to track moving subjects. That means having the autofocus mode set to AF-C (Continuous), or with some cameras, AI Servo. Combined with back-button focus, you simply hold that AF-ON button down with your thumb to keep the AF system active and tracking, and choose when to shoot by pressing the shutter button with your index finger. Nikon D500, Aperture Priority, ISO 800, 1/2000 at f/5.6 in Matrix metering, -0.3 EV, Nikkor 200-500mm f/5.6 lens at 500mm.

Earlier I mentioned the challenge of composing a picture the way you want while also trying to keep that active AF point on your subject, even if it’s not moving. With this system, that’s no longer an issue. If I’m shooting a portrait or landscape, I simply put the active point where the focus needs to be (a person’s eye, a prominent detail in the landscape, etc.) and press the AF-ON button with my thumb. As soon as the camera focuses there, I can release my thumb and shift the framing without worrying about where that AF point is. Now I can concentrate on composition and edges, instead of focus. By removing my thumb from that button I’ve turned off the autofocus, essentially locking focus at that distance. Unless I move or my subject moves, every frame I shoot will be in focus. But that’s not all, there’s one more advantage.

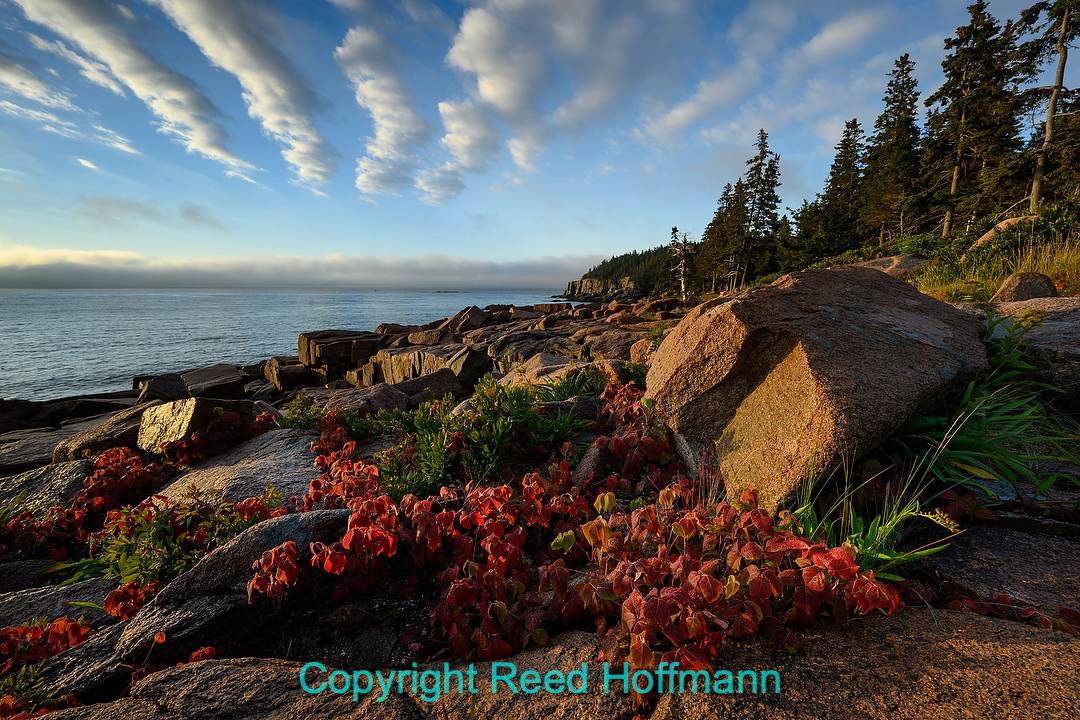

With the camera still set to AF-C and back-button focus, I can press with my thumb to focus on the red leaves in the foreground of this scene in Acadia National Park, then let go and adjust my framing for the composition I want. I don’t need to re-focus unless I move. Nikon Z 7, Aperture Priority, SO 125, 1/20 at f/16 in Matrix metering, -0.3 EV, Nikkor AF Zoom 14-30mm f/4 lens at 14mm.

If you’re shooting static subjects, it’s common to have the AF mode in AF-S (Single Servo). In that case, focus can’t follow, or track a subject. It’s purpose is to find and hold focus at a single point. But what if an interesting bird flies over, and suddenly you’d like to photograph it? That will be a challenge. The camera can’t track in AF-S, and by the time you change modes, the bird is gone. If, however, you’re using back-button focus, there’s no reason to ever be in AF-S. You can keep the camera in AF-C all the time. If the subject’s not moving, simply press the AF-ON button, let it focus and then release. If the subject’s moving (like that bird), press that AF-ON button down and hold it there while you shoot, and the camera will keep tracking the subject. It’s the best of both worlds, an autofocus method that lets you shoot static as well as moving subject with no penalty either way. (At this point some people may say, “What about Auto AF, where the camera decides whether the subject’s moving or not, and reacts accordingly?” You’ll find few, if any, professional photographers who use this method, because they don’t trust the camera to always make the right choice)

So now you understand what “back-button focus” is, and why it’s worth trying. Does this mean all of your pictures will be sharp now? Of course not. No autofocus system is perfect. But they can all be made better, by better understanding how they work and customizing them for your needs. There is a caveat to this, however. I guarantee that if you try this, you’re going to screw up. You’ll start shooting something thinking the camera is focusing when you press the shutter button, just like it used to. And it won’t be. You’ll need some time to practice and adjust to this new way of working with your camera, and remembering to use your thumb to focus. But you know what? If you hate it, go back to what you were doing before.

Photography is like most things in life. There’s rarely just one way to do it “right.” But that’s also one of the great things about photography. You can, and should, try new things. Some will work and some won’t. But your photography won’t get better if you simply keep doing the same things the same way you’ve always done them. Experiment, play, challenge yourself to do new things. That’s how you become a better photographer.

(If you like this story, please share it with your friends and let them know about the links on photography that I post on my business Facebook page. I’m also on Instagram and Twitter, @reedhoffmann. And if you’re curious about the workshops I teach, you can find them here.)

Set up my camera for back button AF about 2 weeks ago. Went out to shoot several days later. Went from shooting macro in manual to AF but could not figure out why my AF lens was not focusing. Double checked the switch on the lens. Tried the usual solution of turning the camera off and on. No luck. Started going through the menus and THEN remembered that I’d set it up for back button AF. I do like it, but it’s not yet a habit for me. Now if I can only get the rest of my failing memory back . . .

Yes, that’s a warning I usually give when telling people about back-button. You’re sure to screw up a few times as you learn a new way of working. Of course, failing is when I learn the most 🙂

Good info on BB focus! Easy to understand.Thanks!